Veterans’ Day Writing Awards Special Program

By Jason Kander - Kansas City. Missouri

Like too many veterans, Jason Kander’s after action battles at home were far more daunting and debilitating than anything he had experienced in Afghanistan. It took 10 years of untreated trauma and the flame-out of a once promising political career to shove Kander onto the path toward understanding and healing.

Like too many veterans, Jason Kander’s after action battles at home were far more daunting and debilitating than anything he had experienced in Afghanistan. It took 10 years of untreated trauma and the flame-out of a once promising political career to shove Kander onto the path toward understanding and healing.

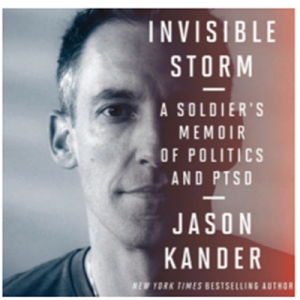

The former Missouri secretary of state and Army intelligence officer also came to realize the power of writing and storytelling as therapy for veterans who struggle with the unrelenting mental torture of combat memories that won’t fade away. Kander, 41, was the keynote speaker for the Veterans Voices Writing Project annual Veterans Pen Celebration 2022 at the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Mo. The suburban Kansas City native’s comments centered mostly on the transformational experience of writing his latest book, Invisible Storm: A Soldier’s Memoir of Politics and PTSD

Crystalizing What I Learned

Kander told his mostly veteran audience that day he had not connected the concepts of writing and therapy until he started preparing his remarks. Then he realized the linkage. “In the process of writing (the book), what ended up happening is that I had to really work hard to crystalize what it was I had learned,” he said. “I had to take what I had learned from therapy and sand it down and get it to a place where I could pass it on to other people, put it in a real book, and that was sort of therapeutic in and of itself.” He cited the second chapter of his book, telling the story of one of his days in Afghanistan, as an early revelation of the power of writing. That ended up being very therapeutic for me because when you’re in the middle of telling a story like that, you’re there,” he said. “There was a therapeutic element. It wasn’t the easiest to release.”

Concern for the Civil-Military Divide

Concern for the Civil-Military Divide

Kander expressed deep concern for what he called the “civil-military divide” in this country and recommended veteran storytelling as one potential antidote. He said combat veterans famously refuse to talk about their experiences because they fear they won’t be understood by civilian relatives and friends who have never served. The only time they feel comfortable talking about combat, he said, is in the company of other veterans.

“We have to get to a place in order to heal that civil-military divide, where that gap isn’t so great and (a veteran) feels like they can talk about it,” Kander said.

“We expect them to be the same person they were before the war. That is not a reasonable expectation. I think we all understand that when you sanitize war you make it a lot harder for those who have returned from war to feel anything but isolation, particularly in a (nation) where less than one percent of the population serves.”

Kander said he appreciated the “public affirmation and reception” he has received for seeking help and writing about it. He said veterans who tell their stories will discover what a difference they can make and how infectious it can be.

Posted in Curating Resources to Help Veterans | From: 2025